-

28 July 2015

- From the section Technology

A new kind of memory technology is going into production, which is up to 1,000 times faster than the Nand flash storage used in memory cards and computers’ solid state drives (SSDs).

The innovation is called 3D XPoint, and is the invention of Intel and Micron.

The two US companies predict a wide range of benefits, from speeding up scientific research to making more elaborate video games.

One expert described it as a “huge step forward”.

“There are other companies who have talked about new types of memory technology, but this is about being able to manufacture the stuff – that’s why they are making such a big deal out of it,” says Bob O’Donnell, from the consultancy Technalysis.

If all goes to plan, the first products to feature 3D XPoint (pronounced cross-point) will go on sale next year. Its price has yet to be announced.

Intel is marketing it as the first new class of “mainstream memory” since 1989.

Rather than pitch it as a replacement for either flash storage or RAM (random access memory), the company suggests it will be used alongside them to hold certain data “closer” to a processor so that it can be accessed more quickly than before.

Why do we need faster storage? The flash storage in my smartphone and PC seems more than fast enough to view and record the photos and videos I want.

Because there are other situations where using today’s storage slows things down or introduces constraints.

So-called “big data” tasks are a particular issue.

For example, efforts to sequence and analyse our genes/DNA hold the potential for new and personalised medical treatments.

But copying the huge amounts of information involved backwards and forwards makes this an extremely time-intensive activity at present.

Faster storage would also help cloud services better handle big files.

That could be helpful in the future, for example, if we wanted to stream 8K ultra-high definition video clips without experiencing lags at their start.

And it would also prove a boon to video game-makers.

At present, level designs are limited by how much data can be stored in the RAM – or, strictly, a type of RAM chip called dynamic RAM (DRAM).

That’s why players sometimes have to halt their play while they wait for the machine to load a new section.

But if the data can be loaded more quickly from 3D XPoint, the developers should, in theory, be able to deliver them bigger, open worlds and a more seamless experience.

OK. Let’s go back to basics – why does it have that weird name?

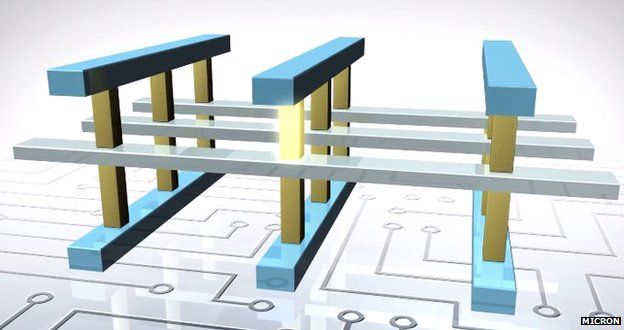

It refers to the fact the technology is made up of a 3D structure featuring layers of wires.

On each layer, the wires run in parallel to each other, but at right-angles to those on the layer below.

In between each layer are vertical sub-microscopic columns, which connect the points at which the wires criss-cross.

Each of these columns contains:

- a “memory cell”, which can store a single bit of data. This represents either a one or a zero in binary code

- a “selector”, which allows a specific memory cell to be read or rewritten. Access is controlled by varying the amount of voltage it receives via the wires

So, what’s the big advantage over flash memory?

3D XPoint does away with the need to use the transistors at the heart of Nand chips.

Nand works by moving electrons back and forth to an isolated part of the transistors known as their “floating gates” to represent the ones and zeros of binary code.

An issue with this technique is that it cannot rewrite single bits of data at a time. Instead, larger blocks of information have to be wiped and then rewritten to incorporate the changes.

“It’s kind of like a parking lot where you want to move one of the cars, but they are all jammed in,” Intel executive Rob Crooke says.

“So, you have to shuffle them all around to get one new one in there.”

By contrast, 3D XPoint works by changing the properties of the material that makes up its memory cells to either having a high resistance to electricity to represent a one or a low resistance to represent a zero.

The advantage is that each memory cell can be addressed individually, radically speeding things up.

An added benefit is that it should last hundreds of times longer than Nand before becoming unreliable.

Sounds great, so is flash storage going to become obsolete?

Intel suggests not.

Solid state drives – and even slower hard disks – will remain significantly cheaper than 3D XPoint for some time to come, so it makes sense to continue using them to store most files.

The suggestion is the new technology will normally be used instead as an intermediary step.

Rather than copy data directly from the slower types of storage into RAM, programs will anticipate what data is likely to be needed and then transfer it in advance to the 3D XPoint.

As a metaphor, imagine a furniture retailer keeps most of its goods in a distant hub that is cheap to run but has slow road links.

It would make sense for it to build a second smaller depot on land that is more expensive but has motorway access, where it could store a selection of its most in-demand items. As a result, it should take less time to restock stores with bestselling goods.

If the 3D Xpoint is so fast, why not just use it to replace RAM altogether?

RAM’s speed advantage over traditional storage has long made it the chip of choice to funnel data directly into processors.

However, because it is relatively expensive to produce, computer makers tend to restrict how much they include.

Each megabyte of 3D Xpoint will certainly be significantly cheaper than the equivalent amount of RAM. And the new technology has the added advantage of being non-volatile, meaning it does not “forget” information when the power is switched off.

But, unfortunately it is still not quite as fast as RAM, and some – but not all – applications need the extra speed the older tech provides.

So, is there ever an advantage to using 3D Xpoint instead of, rather than in addition to, Ram or flash?

Online gaming companies might want to substitute 3D Xpoint for RAM.

At present, the amount of players that can be hosted on a single server is limited by the amount of RAM it contains.

Switching to 3D Xpoint would cause only a small – and possibly unnoticeable – difference to the performance of many of the simpler titles. But it would radically increase the number of people that could be supported for the same price.

One instance when you might want to use the new chips instead of flash would be to store operating system files that are required every time you boot up your machine.

Many users have already experienced faster switch-on times on new computers thanks to such files being kept on SSDs rather than disk drives. A similar performance leap would be experienced by adopting 3D Xpoint.

“It would make for an instant-on experience,” says Intel’s marketing director Greg Matson.

Whether that proves tempting will depend on exactly what 3D Xpoint costs and just how precious your time is.