Five decades after the Vietnam War began—and four decades after it ended— veterans exposed to the chemical brew dubbed Agent Orange are still fighting for compensation and benefits for themselves and their children.

And it turns out, not all veterans exposed to Agent Orange are being treated the same.

The fight is playing out in the halls of Congress, in courtrooms and at veterans meetings across the country.

Agent Orange is the name given to a mixture of toxins used during the Vietnam War to remove leaves from trees and bushes, leaving the enemy more exposed. (It got its name from the orange stripes on barrels containing it.)

All told, about 9 million military personnel served on active duty during the Vietnam era, but most were not stationed in the country. Of those, some 2.6 million were potentially exposed to Agent Orange, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates.

The VA began receiving claims related to Agent Orange exposure in 1977, according to a November 2014 report from the Congressional Research Service. In 1991, Congress passed the Agent Orange Act, which said that certain diseases tied to chemical exposure would be presumed to be related to a vet’s military service and would make the vet eligible for benefits. The list has grown over time and now includes various cancers, diabetes, Parkinson’s Disease, peripheral neuropathy and heart disease, among others.

To get these benefits, though, veterans “must have actually set foot on Vietnamese soil or served on a craft in its rivers (also known as ‘brown water veterans’),” the Congressional Research Service wrote. Those who instead spent time on deep-water Navy ships (called “Blue Water Navy” veterans) do not qualify unless they can show that they spent time on Vietnam land or rivers, the report said.

Below are various groups who receive Agent Orange benefits or are seeking them.

Those Who Served in Vietnam

Since 2002, more than 650,000 veterans have been granted benefits because of their Agent Orange exposure, the VA estimates. (The department did not keep data prior to then.)

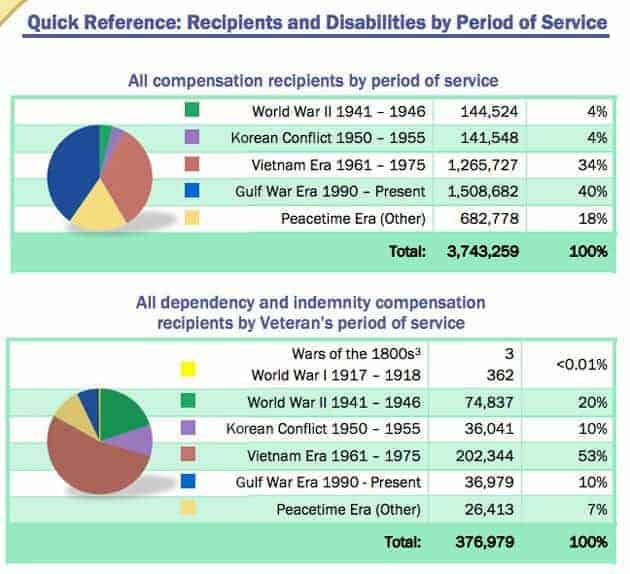

According to the VA’s annual benefits report, it spent nearly $1.3 billion on compensation for Vietnam era veterans in fiscal year 2013, the most recent year for which data is available. That is about one-third of the $3.7 billion in compensation provided that year for all veterans. That figure includes monthly cash compensation payments, but not health care services.

The VA’s website says that: “For the purposes of VA compensation benefits, Veterans who served anywhere in Vietnam between January 9, 1962 and May 7, 1975 are presumed to have been exposed to herbicides, as specified in the Agent Orange Act of 1991. These Veterans do not need to show that they were exposed to Agent Orange or other herbicides in order to get disability compensation for diseases related to Agent Orange exposure.”

Veterans can obtain information on the VA’s website, where they can also file claims for benefits.

Air Force Personnel Exposed to Contaminated C-123 Aircraft

In June, the VA expanded benefits to Air Force and Air Force Reserve personnel who served as flight, medical and ground maintenance crew members on C-123 aircraft that were used to spray Agent Orange. These troops, estimated to number between 1,500 and 2,100, will be eligible for benefits if they have a health condition from the same list that applies to on-the-ground troops.

This followed a report earlier this year from the national Institute of Medicine, which found that “some reservists quite likely experienced non-trivial increases in their risks of adverse health outcomes.”

“Opening up eligibility for this deserving group of Air Force veterans and reservists is the right thing to do,” VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald said in a statement in June.

Two other senators, Richard Burr, R-N.C., and Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., had long pushed the VA to provide benefits to C-123 veterans.

“The effort of these veterans to secure overdue VA care and benefits for harmful exposure to Agent Orange has not been one of the agency’s finest hours,” Burr said in a statement. “This frustrating, four year process has laid bare the lengths that the VA will go to disregard science and the facts of the historical record. I am pleased Secretary McDonald has chosen to finally do the right thing for these ailing veterans, but it shouldn’t have been this hard or taken so long.”

Blue Water Veterans

The VA does not currently provide Agent Orange benefits to an estimated 90,000 “blue water” veterans who say they were exposed to the chemical in their drinking water while working on Navy ships off the coast of Vietnam.

In 2002, a VA report found there was insufficient evidence to connect health problems of blue water sailors with chemical exposure aboard ships, establishing the basis for denying benefits to vets who didn’t set foot in Vietnam. That decision was upheld by a federal appeals court in 2008. A 2011 report by the Institute of Medicine, however, identified several “plausible routes” for Agent Orange exposure through the water distillation process aboard Navy ships, as well as through the air.

Such vets can only receive Agent Orange-related benefits if they show “on a factual basis” that they were exposed to the chemicals during their military service.

Following the decision last month to grant Agent Orange benefits to C-123 crews, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., said the VA should do the same for blue water Navy vets. Bills introduced in the Senate and House this year would extend presumptive Agent Orange health coverage to sailors who served in territorial waters as far as 12 miles from the Vietnam coast.

“We owe it to the veterans who bravely served our country and have fallen victim to Agent Orange-related disease to enact this legislation that will provide the disability compensation and healthcare benefits they have earned,” Gillibrand said in a statement.

In April, the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims struck down VA rules that denied presumptive Agent Orange compensation for sailors whose ships docked at the harbors of Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay and Vung Tau. Those ports, the court determined, were in the Agent Orange spraying area. The VA is not appealing the ruling.

Those Who Served Elsewhere

Veterans who served in or near the Korean demilitarized zone between April 1968 and August 1971 and who have a disease associated with Agent Orange are entitled to benefits under VA rules that took effect in 2011.

The VA acknowledges that vets stationed at Air Force bases in Thailand between 1961 and 1975 may have been exposed to Agent Orange, which was sprayed along the perimeters of the installations. But those who served at bases in Thailand must prove they performed duties that may have led to exposure.

Lawyers who routinely argue on behalf of Vietnam-era veterans seeking benefits say it can be difficult to satisfy the VA’s requirement for proving exposure in Thailand. For example, Army veterans must produce documentation showing their duties sent them to the outskirts of a base, either through written orders, statements from fellow veterans, or through photographic evidence, lawyers said.

Children of Veterans

For decades, Vietnam veterans have voiced concern that their Agent Orange exposure has led to health issues for their children and grandchildren. Over the past three years, Vietnam Veterans of America has recorded hundreds of testimonials from offspring of Vietnam veterans who believe their health has been affected by a parent’s exposure. The VA, though, says there’s insufficient research to make a scientific connection.

Despite that, the VA provides benefits for a limited number of birth defects in children of Vietnam veterans, including spina bifida for children of all vets (male and female) and 18 other health conditions solely for children of female vets. To date, about 1,200 children with spina bifida have received those benefits, along with 14 children of female veterans with other covered birth defects, according the VA.

In its most recent report to the agency, published in 2013, the Institute of Medicine concluded that “a connection between toxin exposure and effects on offspring, including developmental disruption and disease onset in later life, is biologically plausible.” The report recommended further study.

Bills pending in the Senate and House would create a national research center to study medical conditions that arise in the descendants of those exposed to toxic substances during military service, not only in Vietnam, but also in the Gulf War, Afghanistan and Iraq.

“When an individual serves their country in the military, I would assume that they recognize the challenges and the sacrifices that they may make,” said Sen. Jerry Moran, R-Kan., during a Committee of Veterans Affairs hearing last month. “When something happens to them, it’s a terrible thing. But I cannot imagine the pain or concern that comes to a father or a mother who now sees the consequence of their military service now affecting their children or their grandchildren.”

The legislation has the backing of many veterans organizations, but the VA opposes the bill. Rajiv Jain, a VA assistant deputy under secretary for health, told lawmakers last month that other federal agencies are better suited to research the effects of toxic exposure. Further, Jain testified, “a proposed center focusing solely on military toxic exposures would likely not have the statistical basis to support conclusive findings.”