By Drew Johnson, Urban News Service

L.A. schools lost a billion dollars on a failed tech experiment. Students got iPads that taught them nearly nothing.

The Los Angeles Unified School District began delivering curriculum materials to students using Apple iPads in 2013. The devices were supposed to replace school books, foster interactive study and streamline test taking. But teachers, district officials and taxpayers now call this plan a pricey flop.

The failed program triggered an FBI investigation, prompted the resignation of the district’s superintendent and left countless school-repair and construction projects unfinished.

The iPad program initially cost $1.3 billion – $500 million for the devices and educational software from publishing giant Pearson and another $800 million to upgrade the district’s computer networks. That outlay only financed 120,000 iPads, for about 20 percent of district students. This left more than 650,000 children behind.

L.A. funded the iPad experiment with 25-year school-construction bonds. Thus, with interest, the final taxpayer expenditure could exceed $2 billion – on equipment that typically has a three-year lifespan.

The district’s purchase of iPads via construction bonds leaves L.A. with far less money to repair and replace deteriorating schools, especially in poor and minority neighborhoods. That clearly riled many teachers.

Two local instructors formed the “Repairs, Not iPads” Facebook page. Teachers used it to display pictures of neglected maintenance in their schools.

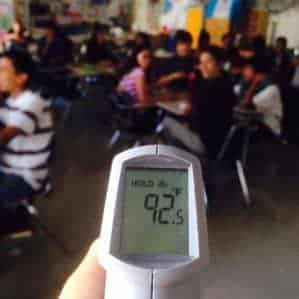

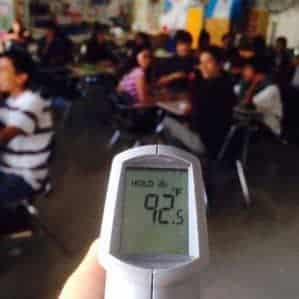

One photo shows a digital thermometer reading 92 degrees inside a classroom with an overwhelmed air-conditioning system. Other pictures show broken toilets, a dangerously exposed electrical outlet and cockroaches in classrooms.

One photo shows a digital thermometer reading 92 degrees inside a classroom with an overwhelmed air-conditioning system. Other pictures show broken toilets, a dangerously exposed electrical outlet and cockroaches in classrooms.

Several snapshots feature leaky roofs and even flooded classrooms.

“If you came home to see this kind of flooding in your home, would you think that it is time to buy everyone in the family a new iPad?” asked Matthew Kogan, who teaches at Chinatown’s Evans Community Adult School.

The iPad program’s problems outpaced its budget. Once students received the devices, complications multiplied. Within days, high school students hacked into them, bypassed security controls, and then played games and visited Twitter, Facebook and YouTube.

The fragile machines also broke in teenaged hands.

When many parents were unable to pay the iPads’ $768 replacement cost, thousands of low-income students could not follow along in class or do homework.

Pearson’s software platform suffered technical glitches and offered incomplete curriculum programs. Hence, teachers rarely had enough working iPads in classrooms, leaving some students – and sometimes, entire classes –frittering away days of valuable learning time.

The frustration grew so great that, by the end of the project’s first academic year, only two of 69 participating schools still used the devices, according to project director Bernadette Lucas. The other schools had “given up on attempting regular use of the app,” she said.

School district leaders soon unplugged the iPads, barely two years after they were clicked on.

“While Apple and Pearson promised a state-of-the-art technological solution for [the iPad program’s] implementation, they have yet to deliver it,” school district attorney David Holmquist wrote to Apple’s general counsel last April, announcing the project’s termination. “As we approach the end of the school year, the vast majority of students are still unable to access the Pearson curriculum on iPads.”

But not even the program’s cancellation stopped its woes. Some observers wondered why the district paid $768

for iPads that retail for as little as $250. The Los Angeles Times and Pasadena public-radio station KPCC

revealed e-mails in which L.A. school superintendent John Deasy quietly agreed to work with Apple and Pearson more than a year before unveiling the program.

The FBI is now investigating the iPad contracts for improprieties. Also, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission is probing whether school leaders properly disclosed that bonds would fund the effort.

Deasy resigned as superintendent in October 2014, largely due to the failed iPad experiment and the alleged wrongdoing involved in granting contracts to Apple and Pearson. But even post-Deasy, many taxpayers, who are still on the hook for the scrapped program, remain furious.

“Taxpayers are getting fed up with this kind of irresponsibility because they know it is damaging the academic success of their children,” said Lydia Gutierrez, a board member of the Coastal San Pedro Neighborhood Council.

The school district got some money back from Pearson and Apple, because the companies did not fulfill their contracts. Pearson agreed to refund $6.4 million for failing to provide completed math and English curricula. Apple paid $4.2 million after the district threatened to sue over faulty software.

For its part, Pearson says the curriculum was complete, but the company had “important enhancements to add,”

which were scheduled to occur twice a year, according to Pearson spokesman Brandon Pinette. The contract’s cancellation made those improvements moot.

L.A.’s failures contrast with other schools and districts that successfully harnessed the Internet to offer students more personalized education.

Ohio’s Hilliard City Schools, Seattle’s Highline Public Schools, and Boulder, Colorado’s Valley School District are just a few places that have improved learning via tablet and notebook computers, and related software, at a fraction of what Los Angeles misspent.

Milpitas Unified School District also earned praise. The urban San Francisco Bay Area jurisdiction, where about half the students are immigrants, let teachers and principals decide how to incorporate technology. L.A.’s school officials, in contrast, imposed a rigid, top-down approach.

Milpitas officials provided students inexpensive Chromebooks, which usually retail for between $180 and $240. Milpitas principals discovered they didn’t need to give each child a tablet. Rotating students in shifts let the district save money by buying fewer devices. This also gave students more direct, offline

contact with teachers.

These achievements suggest that Los Angeles’ educators learned little before launching their iPad venture. This frustrates Ben Barker, an Angeleno and parent of a district student.

“At the end of the day, school district leaders still [threw] away over $1 billion on iPads that didn’t work, and a lot of kids went weeks without learning a thing,” Barker said. “The whole thing was a craptastic embarrassment and a disaster.”