-

14 July 2015

- From the section Science & Environment

Tension is mounting as scientists await confirmation that a flyby of Pluto by the New Horizons probe was successful.

The spacecraft turned its antenna away from Earth during Tuesday’s flyby to gather data on its target.

It is expected to call home at 01:53 BST on Wednesday; controllers should be able to quickly tell whether the flyby sequence worked properly or not.

New Horizons should be storing high-resolution images and other data from the pass in its onboard memory.

The probe was due to start sending engineering data at 20:27 GMT (21:27 BST). But New Horizons is currently about 4.7 billion km from Earth and at this separation, a light signal takes about four hours and 25 minutes from transmission to receipt.

Key moment

Earlier on Tuesday, scientists and engineers cheered as the probe hurtled past the planet at 11:50 GMT (12:50 BST). It was due to fly about 12,500km from the surface of the little world.

The first high-resolution pictures from the flyby – with about 10 times the detail of those already published – should be downlinked later on Wednesday.

New Horizons’ flyby of 2,370km-wide Pluto is a key moment in the history of space exploration.

It marks the fact that all nine objects considered by many to be the Solar System’s planets – from Mercury through to Pluto – have now been visited at least once by a probe.

“We have completed the initial reconnaissance of the Solar System, an endeavour started under President Kennedy more than 50 years ago and continuing to today under President Obama,” said the mission’s chief scientist, Alan Stern.

Prof Stephen Hawking sent a message of congratulations to the team, saying: “The revelations of New Horizons may help us to understand better how our Solar System was formed. We explore because we are human and we want to know.”

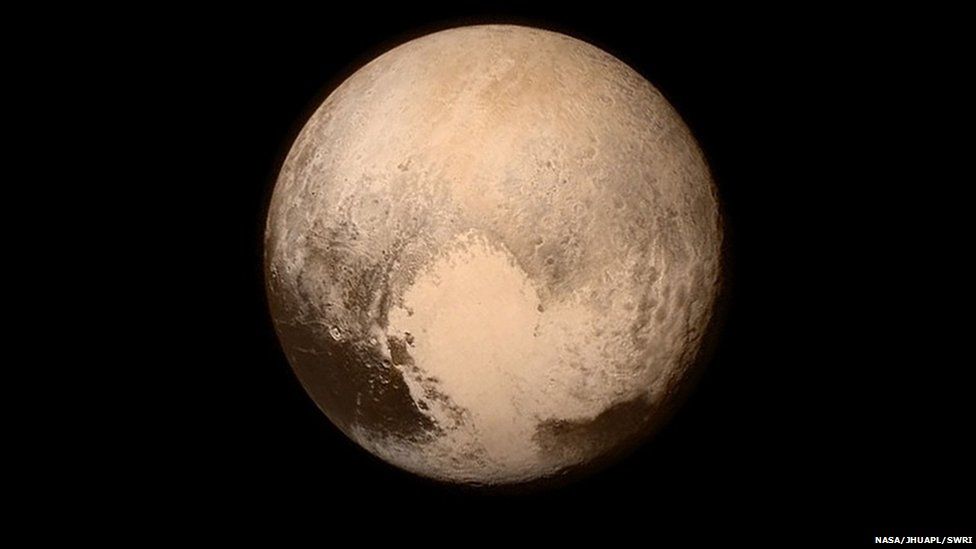

Surface features evident in images returned during New Horizons’ approach to the dwarf planet have already become the source of intense speculation.

The world has a bright, heart-shaped region and dark patches near its equator, which have been informally described as “the whale”.

Analysis – David Shukman, science editor

There’s something refreshingly raw about covering this extraordinary and uplifting story. As we catch the scientists in the corridors or listen in to their briefings, one impression is overwhelming: that they’re blissfully ignorant about what’s hitting them and are rather enjoying the novelty of not being able to explain anything.

This is because the Pluto venture is discovery in its purest, least processed and most thrilling form. We’re experiencing the cosmic equivalent of landing on a totally unexplored shore. I keep picturing someone like Charles Darwin startled by a strange animal and having no frame of reference to even begin to understand it. Pluto and its moons are so unknown that every hour seems to bring more surprises. And, when we ask questions, we no longer expect confident answers but have become used to hearing an amused “don’t know”.

Other favourite phrases include “well, that’s just an idea” and “this is our first attempt on the back of an envelope”. One that may become classic was the scientist who started to offer an explanation before admitting with a chuckle that he was only thinking of a theory and that “he was making it up right now”. Everyone laughed with him. And this makes the mission all the more exciting. Usually us journalists are dealing with finished, polished research findings. Not here. We all feel like we’re on the journey of discovery too.

Prof Stern said: “On the surface we see a history of impacts, we see a history of surface activity in terms of some features we might be able to interpret as tectonic – indicating internal activity on the planet at some point in its past, and maybe even in its present.

“This is clearly a world where geology and atmosphere – climatology – play a role. Pluto has strong atmospheric cycles. It snows on the surface. These snows sublimate – go back into the atmosphere – every 248-year orbit.”

The post-flyby call home will come through a giant dish in Madrid, Spain – part of Nasa’s Deep Space Network of communications antennas.

There is a very small possibility that New Horizons could be lost as it flies through the Pluto system.

Any stray icy debris would have been lethal if it had collided with the spacecraft at its 14km/s velocity (31,000mph).

“Hopefully it did [survive],” said Prof Stern, “but there is a little bit of drama.”

The BBC will be screening a special Sky At Night programme called Pluto Revealed on Monday 20 July, which will recap all the big moments from the New Horizons flyby.

Follow Paul and Jonathan on Twitter.