Roddy Scheer and Doug Moss December 9, 2021

Dear EarthTalk: Has anyone calculated the positive health and/or economic impacts of international efforts to protect the stratospheric ozone layer beginning in the late 1980s?

—C. Marin, St. Louis, MO

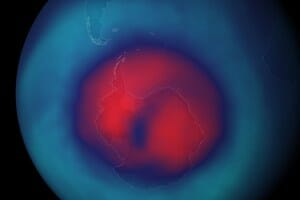

1987’s Montreal Protocol, a landmark international agreement calling on the nations of the world to ban the production and distribution of man-made chemicals that deplete the stratospheric ozone layer, has been billed as one of the greatest examples of international cooperation to date. And while everyone party to the Montreal agreement agreed that the substance of the treaty—banning so-called chlorofluorocarbons and related ozone-stripping chemicals—was a big win for the environment and human health, we have had no idea how to quantify just how many lives have been saved or improved as a result.

Until now, that is. Researchers from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), ICF Consulting, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that the Montreal Protocol and its subsequent amendments will have prevented some 443 million cases of skin cancer and 63 million cases of cataracts in the U.S. alone by the end of the 21st century. They used computer models to plot how much ultraviolet (UV) radiation would have reached the Earth’s surface through holes in the ozone layer without the ban on CFCs and other fluorocarbons, extrapolating from there.

“We peeled away from disaster,” NCAR scientist Julia Lee-Taylor, a co-author of the study, told ScienceDaily. “What is eye popping is what would have happened by the end of this century if not for the Montreal Protocol.” According to projections from the researchers’ modeling, without the agreement, UV radiation would triple by 2080. “After that, our calculations for the health impacts start to break down because we’re getting so far into conditions that have never been seen before.”

“It’s very encouraging.” she added. “It shows that, given the will, the nations of the world can come together to solve global environmental problems.”

Indeed, recent attempts to forge a global carbon drawdown have the potential for perhaps even bigger health impacts for the human race (and others) moving forward. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers global warming the greatest health threat ever facing humanity. This United Nations-backed international body charged with directing and monitoring global public health initiatives expects climate change to cause 250,000 additional deaths per year from a combination of factors including malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea and heat stress. Additionally, global warming will end up tacking some $2-$4 billion per year onto our global health care bill. And sadly, but not surprisingly, lesser developed countries and regions will fare worse given their weaker health infrastructures.

Indeed, the success of the Montreal Protocol and the urgency of the climate crisis provide all the reasons we need to encourage the leaders of the United States and other nations around the world to forge ahead with the strongest possible international climate agreement with binding and meaningful emissions reduction targets. Our future may very well depend upon it.

CONTACTS

EarthTalk® is produced by Roddy Scheer & Doug Moss for the 501(c)3 nonprofit EarthTalk. See more at https://emagazine.com. To donate, visit https//earthtalk.org. Send questions to: question@earthtalk.org.