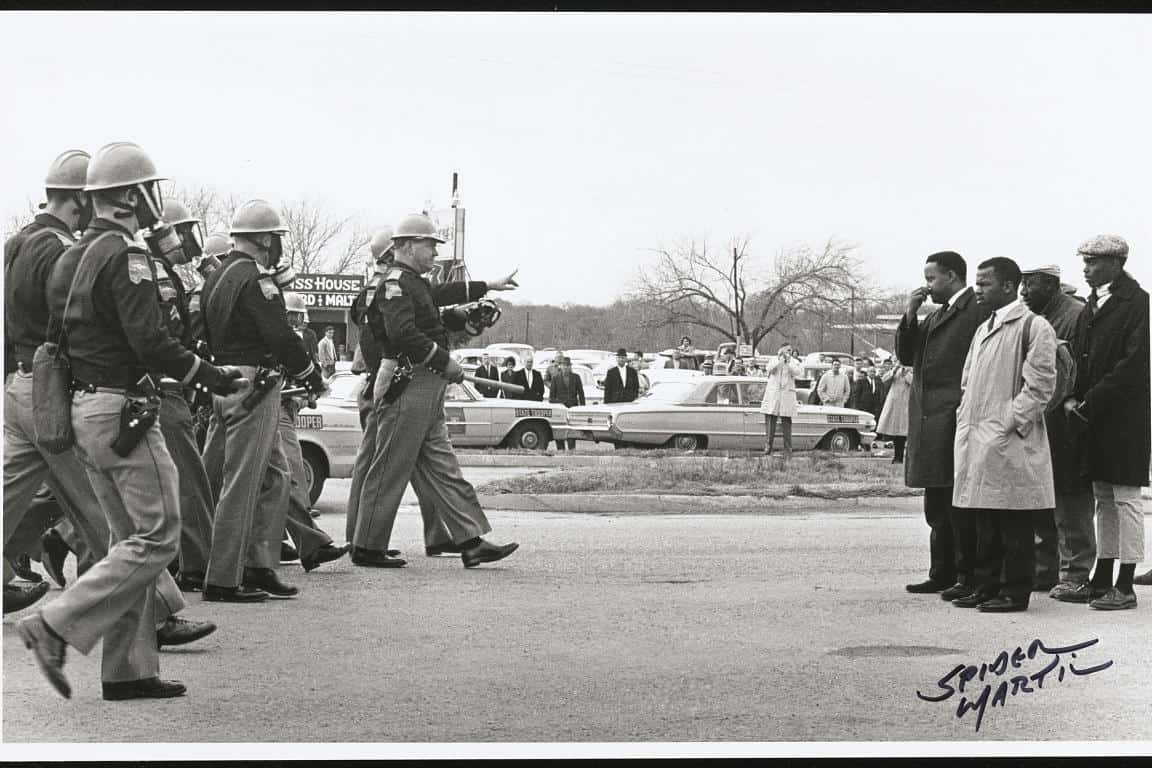

THE CHICAGO CRUSADER — On Sunday, March 7, 1965 in Selma, Alabama, Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams led hundreds of marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. They were on their way to the state capitol fighting for the right to vote. On the other side of the bridge were the Alabama State Troopers on horses. After crossing the bridge, the troopers attacked marchers and beat Lewis with a club. He suffered a fractured skull that nearly killed him. The incident became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Crusader Staff Report

The life and legacy of Congressman John Lewis is being remembered as the nation mourns the death of the civil rights activist, political giant, and a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus who died July 17 from pancreatic cancer. He was 80.

He fought for the voting rights of millions of Blacks and was responsible for the birth of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Today, Lewis leaves a powerful legacy in Black history and American politics.

His death closes a chapter of Black leadership from a generation that saw unprecedented change for Black America.

That era also included Civil Rights giant Reverend Cordy Tindell “CT” Vivian, 95, who died hours before Lewis. Rev. Vivian was renowned for participating in Freedom Rides and sit-ins and advocating for Black voting rights. Vivian died hours before Lewis. Last March, Joseph Lowery, another luminary of the Civil Rights movement, who founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., died after decades of fighting for Civil Rights.

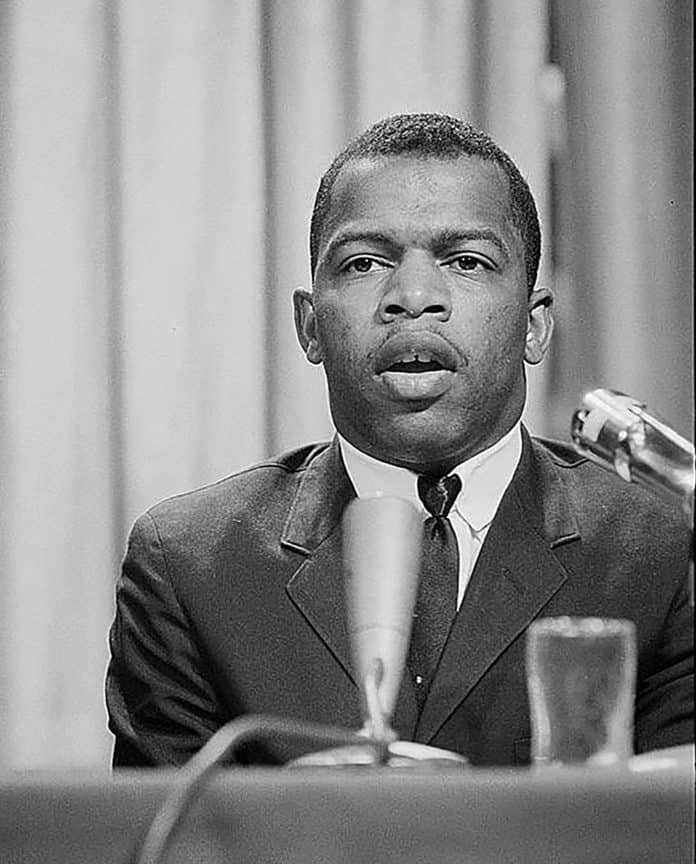

Lewis was the youngest and last survivor of the “Big Six” civil rights activists who led numerous marches, protests and sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. During his three decades as U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, Lewis became the “moral conscience” of the U.S. House as he campaigned for legislation that advanced the agenda of America’s minorities, poor and forgotten.

As flags fly at half-staff across the nation to honor Lewis, former U.S. Presidents, Congressional leaders and both Democrat and Republican lawmakers are paying tribute to a leader whose spirit and courage smashed racial barriers that led to millions of Blacks gaining the right to vote. Leaders are planning a fitting memorial that may include Lewis becoming the second Black person to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol building. There is also a push to rename the Edmund Pettus Bridge after Lewis, who led a group of Blacks on the site during the infamous “Bloody Sunday” march in 1965.

As plans for Lewis’ homegoing service take shape, tributes from America’s prominent leaders continue to pour in.

Reverend Jesse Jackson, Sr. said, “John Lewis will be remembered for his humility. He was a kind and decent man. He was generous with his time for others. He had become the conscience of the nation.”

Former President Barack Obama said, “It’s fitting that the last time John and I shared a public forum was at a virtual town hall with a gathering of young activists who were helping to lead this summer’s demonstrations in the wake of George Floyd’s death. I told him that all those young people—of every race, from every background and gender and sexual orientation—they were his children. They had learned from his example, even if they didn’t know it. They had understood through him what American citizenship requires, even if they had heard of his courage only through history books.”

The national headquarters of the NAACP headed by CEO Derrick Johnson, said in a statement, “John Lewis was a national treasure and a civil rights hero for the ages. We are deeply saddened by his passing but profoundly grateful for his immense contributions to justice.”

Marc Morial, President and CEO of the National Urban League said, “John was also a personal hero, a friend and a mentor. In 2013, the National Urban League recognized him with our highest honor, the Civil Rights Champion Award. In his presence, I was reminded that I stand on the shoulders of history.”

Lewis was born on February 21, 1940 in Troy, Alabama. His parents, Eddie Lewis and Willie Mae (nee Carter), were sharecroppers who worked to own their own farm. Lewis and his nine siblings worked regularly on the family’s farm, instead of attending the county’s segregated schools in the Deep South.

In 1957, when he was 18, Lewis wrote a letter to Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after he was inspired by Rosa Parks and the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. A year later in 1958 when the two met on the steps of Reverend Ralph Abernathy’s church, Dr. King said, “So you are John Lewis, the boy from Troy” and that’s how he often referred to him thereafter.

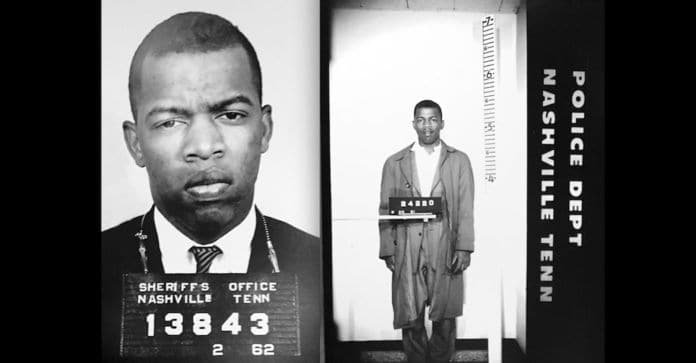

Without his family’s knowledge, Lewis became involved in the Civil Rights Movement as a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, where he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization that he helped form.

After graduating in 1961, Lewis enrolled in Fisk University, a historically Black school in Nashville. As a student at Fisk University, Mr. Lewis was a part of the Nashville Student Movement and helped organize sit-ins that eventually led to the desegregation of the lunch counters in downtown Nashville.

In 1961, he became one of the 13 original Freedom Riders, an integrated group determined to ride from Washington, DC to New Orleans. In 1963, he became the Chair of SNCC. As Chair of SNCC, Lewis joined King, A. Phillip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young and James Farmer as the “Big Six” Civil Rights leaders who brought hundreds of thousands to the historic March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Lewis was the youngest leader to speak about jobs and freedom that day.

On Sunday, March 7, 1965 in Selma, Alabama, Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams led hundreds of marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. They were on their way to the state capitol fighting for the right to vote. On the other side of the bridge were the Alabama State Troopers on horses. After crossing the bridge, the troopers attacked marchers and beat Lewis with a club. He suffered a fractured skull that nearly killed him. The incident became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

The march was one of several that led President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Lewis was elected to his first governmental office in 1981, serving as an Atlanta City Council member until 1986. That year, he was elected to Congress and immediately had a vision of an African American Museum of History and Culture. He introduced the legislation in 1988, but the bill was blocked by Senator Jesse Helms for 15 years. Lewis finally got it passed in 2003. He lived to see it completed and opened in September 2016.

In 2012, John Lewis unveiled a marker in Emancipation Hall commemorating the contributions of enslaved Americans who built the U.S. Capitol building. The marker capped a decade-long effort led by Lewis and a special task force.

At the unveiling ceremony, Lewis said “When I walk through Statuary Hall, it means a great deal to me to know that the unusual grey marble columns were likely hewn and polished by slaves in Maryland. They quarried the stone in Maryland and sailed ships or barges many miles down the Potomac River weighed down by heavy marble columns to bring them to DC. These men and women played a powerful role in our history and that must not be forgotten.”

Legislatively, Mr. Lewis championed the Voter Empowerment Act, which would modernize registration and voting in America and increase access to the ballot. He was also an ardent advocate for immigrants, the LGBTQ community, and affordable health care for all. As Chair of the Oversight Subcommittee on the House Ways and Means Committee, Lewis helped ensure the efficient implementation of laws related to tax, trade, health, Human Resources, and Social Security. He examined how the tax code subsidizes hate groups and addressed the impact of gun violence on public health. Most recently, Lewis pressed the Trump Administration to quickly deliver the stimulus checks that Congress provided in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Mr. Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States of America. Following the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida in 2016, John Lewis led Democrats in a 26-hour sit-in on the House floor to demand that the body debate gun control measures. Every year, he led a pilgrimage to Selma to commemorate the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which was named after a Confederate soldier and a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

This article originally appeared in The Chicago Crusader.