By DARA KAM, The News Service of Florida | THE CAPITAL, TALLAHASSEE– It’s not unusual for lawyers representing Death Row prisoners whose execution dates have been set to file last-minute appeals to try to get more time to argue about why their clients should be spared.

But an attempt by death-penalty lawyer Marty McClain on behalf of Mark James Asay, scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection late this month, is even more complicated.

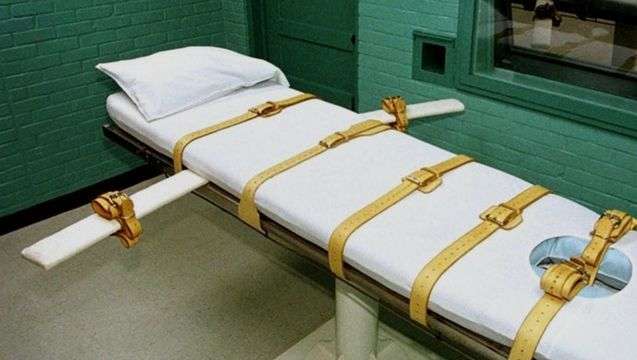

For one, McClain is challenging a new triple-drug lethal injection formula, never before used in Florida or any other state.

In addition, McClain — who’s represented more than 200 condemned prisoners over the past three decades — is accusing the state of hoodwinking him into agreeing to a legal delay that could cost his client a review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Gov. Rick Scott last month rescheduled Asay’s execution for Aug. 24, more than 18 months after originally signing a death warrant for the Death Row prisoner, who was sentenced to death nearly three decades ago.

Asay was one of two Death Row inmates whose executions were put on hold by the Florida Supreme Court in early 2016 after the U.S. Supreme Court, in a case known as Hurst v. Florida, struck down as unconstitutional the state’s death penalty sentencing system. Lawmakers later revamped the sentencing system.

Asay was convicted in 1988 of the murders of Robert Lee Booker and Robert McDowell in downtown Jacksonville. Asay was accused of shooting Booker, who was black, after calling him a racial epithet. He then killed McDowell, who was dressed as a woman, after agreeing to pay him for oral sex. According to court documents, Asay later told a friend that McDowell had previously cheated him out of money in a drug deal.

A Jacksonville judge on Friday rejected a request by Asay to put the execution on hold. Asay’s lawyer challenged, among other things, a new drug protocol adopted by the Florida Department of Corrections this year.

In the new protocol, Florida is substituting etomidate for midazolam as the critical first drug, used to sedate prisoners before injecting them with a paralytic and then a drug used to stop prisoners’ hearts.

In a 30-page order issued Friday, Duval County Circuit Judge Tatiana Salvador ruled that Asay failed to prove that the new three-drug protocol is unconstitutional.

Etomidate, also known by the brand name “Amidate,” is a short-acting anesthetic that renders patients unconscious. Twenty percent of people experience mild to moderate pain after being injected with the drug, but only for “tens of seconds” at the longest, the judge noted.

“Defendant has only demonstrated a possibility of mild to moderate pain that would last, at most, tens of seconds,” Salvador wrote. “Therefore, this court finds the potential pain and anesthetic aspect of etomidate does not present risks that are ‘sure or very likely’ to cause serious illness or needless suffering or give rise to ‘sufficiently imminent dangers.’ ”

Salvador rejected a request by McClain for a rehearing on Friday’s order, but the lawyer’s motion gives a glimpse into arguments he can be expected to present to the Florida Supreme Court as Asay’s case winds its way up the judicial chain.

Asay argues that the state failed to provide him notice of the revamped lethal injection protocol, essentially keeping McClain from having enough time to present evidence at the circuit court hearing last week.

McClain also argues that the Jacksonville judge failed to fully consider the implications of a U.S. Supreme Court decision, in a case known as Glossip v. Gross, focused on lethal injection protocols.

That ruling requires prisoners challenging lethal injection procedures to establish that “any risk of harm was substantial when compared to a known and viable alternative method of execution.”

McClain argues that, instead of the new drug protocol, corrections officials should use the three-drug lethal injection procedure involving midazolam, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride that was in effect when Asay’s original death warrant was signed last year, or a single-drug protocol adopted by some other death-penalty states.

Despite numerous challenges to the use of midazolam as the first drug in the lethal injection process, courts have repeatedly upheld its use, McClain wrote.

Etomidate is another matter, he wrote.

“It carries a risk of pain and a risk of seizure-like movements as Mr. Asay dies. This raises Eighth Amendment bases to challenge both the substantial risk of pain and the undignified manner of death,” he wrote.

The use of etomidate — which could cause pain for up to 20 seconds — “creates a risk that is substantial harm when compared to known and available alternative methods of execution,” McClain added, referring to the standard laid out in the Glossip ruling.

The change in the protocol has come as states have scrambled to obtain lethal-injection drugs because manufacturers have refused to sell the substances to corrections agencies for execution purposes.

Florida Department of Corrections officials maintain that the use of etomidate is “compatible with evolving standards of decency,” a standard used by the courts in evaluating death penalty procedures.

“The process will not involve unnecessary lingering or the unnecessary or wanton infliction of pain and suffering. The foremost objective of the lethal injection process is a humane and dignified death,” Department of Corrections spokeswoman Michelle Glady said in an email, quoting from the agency’s lethal injection protocol adopted earlier this year, when asked about Asay’s latest motion.

In another issue in the case, McClain argues that Attorney General Pam Bondi’s office, which represents the state in death penalty cases, used its power to “obtain a strategic advantage” by getting him to sign off on a legal delay.

In a letter to Scott last month, McClain argued that Bondi had misrepresented the status of the case when she gave the governor a go-ahead for scheduling the execution.

After McClain filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, known as a “writ of certiorari,” this spring, Bondi sought a 30-day extension in the case.

McClain said he interpreted Bondi’s request for a postponement, to which he agreed, to mean that the state would not seek a new execution date for Asay until after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the appeal this fall.

Without the 30-day extension, the U.S. justices could have taken up Asay’s appeal before their summer hiatus, which started on June 28 and lasts until October, McClain argued.

Instead, the court gave Bondi until July 5 to file her response to Asay’s request.

Two days before the deadline, Bondi certified to Scott that Asay was eligible for execution. After Scott signed Asay’s death warrant on July 3, setting the execution date for Aug. 24, Bondi quickly filed an objection to Asay’s appeal in the U.S. court.