NNPA NEWSWIRE — These posters sent a message to Black veterans that they need not apply — that these life-changing programs were not meant for them. This message was reinforced by the blatant discrimination perpetrated by Veterans Affairs (VA) offices around the country and the abysmal benefits provided to veterans of color.

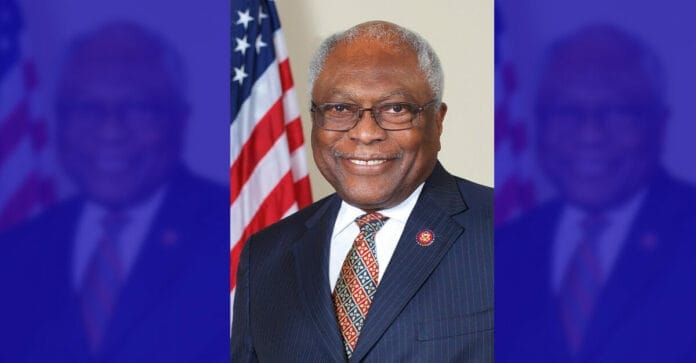

by Assistant Democratic Leader James E. Clyburn, via BlackPress of America

The original government-issued posters publicizing the G.I. Bill of 1944 were designed to inspire. Oversized red and white letters urged, “Veterans — prepare for your future through EDUCATIONAL TRAINING. Consult your nearest Office of the VETERANS ADMINISTRATION.” Another read, “VETERANS — if buying a farm, home, or business, learn about GUARANTEED LOANS.” A third showed a young man with his hand on his chin, deep in thought, with the following text above: “Shall I go back to school?”

What’s notable about these posters is that every person pictured is white. These posters sent a message to Black veterans that they need not apply — that these life-changing programs were not meant for them. This message was reinforced by the blatant discrimination perpetrated by Veterans Affairs (VA) offices around the country and the abysmal benefits provided to veterans of color. In 1947, only two of more than 3,200 home loans administered by the VA in Mississippi cities went to Black borrowers. Similarly, less than 1% of VA mortgages went to Black borrowers in New York and New Jersey suburbs.

These disparities in homeownership opportunities have grown with time. The Consumer Federation of America estimates that homeownership rates for white and Black Americans stood at 74.50% and 44.10% respectively in 2020, and 65% and 38% in 1960. This homeownership disparity helps explain the difference in net worth for white families ($171,000) compared to that of Black families ($17,150). After signing the G.I. Bill into law in June 1944, President Truman remarked that it would give “emphatic notice to the men and women in our armed forces that the American people do not intend to let them down.”

Nearly 80 years later, I’ve teamed up with Congressman Seth Moulton (MA-06) and U.S. Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock (D-GA) to ensure President Truman’s words ring true. We have reintroduced Sgt. Isaac Woodard, Jr. and Sgt. Joseph H. Maddox G.I. Bill Restoration Act in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. It would provide critical housing and education benefits to Black World War II veterans and their descendants, honoring our long overdue promise to the nation’s heroes. It would also require that the Government Accountability Office establish a panel of independent experts to assess inequities in how benefits are distributed to minority and female service members.

The bill’s name pays homage to two admirable and unsung World War II veterans. In February 1946, decorated World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard, Jr. was traveling home on a Greyhound bus to Winnsboro, South Carolina when a local police chief forcibly removed him from the bus. Still in his uniform after being honorably discharged, the officer beat him mercilessly. Woodard was cruelly thrown in jail rather than given the necessary medical treatment, leading to his blindness. The police chief was ultimately acquitted of the crime by an all-white jury. President Truman was so moved by Sgt. Woodard’s horrific abuse that he signed an Executive Order integrating the armed services.

Sgt. Joseph Maddox, another World War II veteran, applied and was accepted to a master’s degree program at Harvard University. His local Veterans Affairs office denied him the tuition assistance he was rightfully due under the G.I. Bill to “avoid setting a precedent.” After seeking assistance from the NAACP, the VA in Washington, D.C., ultimately promised to get Sgt. Maddox the educational benefits he deserved.

These are just two of the countless servicemembers who were treated unfairly after sacrificing on behalf of their country. Black soldiers returning home from World War II found themselves facing the same socioeconomic and racial discrimination they had faced before. Instead of being welcomed with open arms, they struggled to find jobs, get educated, and purchase homes. We cannot undo the injustices of our past. But we can begin to restore the possibility of full economic mobility for those that the original G.I. Bill left behind. The G.I. Bill Restoration Act would bring us one step closer to that goal.