The Seraaj Report, by Kevin Seraaj

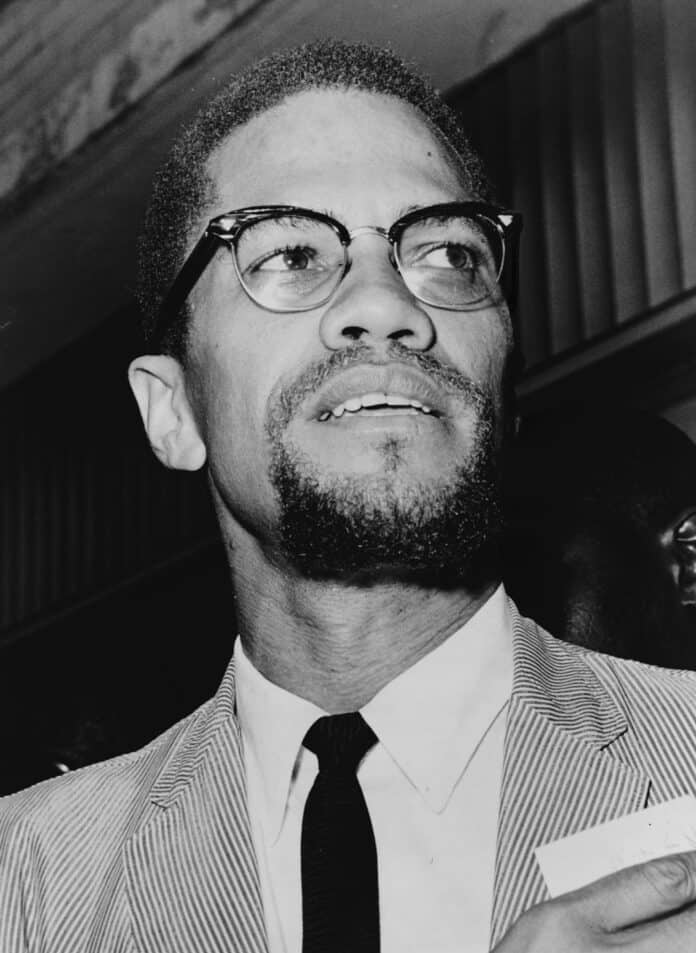

On February 21, 1965, former civil rights leader Malcolm X was gunned down by a man wielding a sawed-off shotgun while giving a speech in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom. Two other men with handguns fired on Malcolm, contributing to the 21 gunshot wounds later found on his body by the medical examiner.

Nation of Islam member Talmadge Hayer (later known as Mujahid Abdul Halim), was captured by members of the crowd at the scene and beaten before police arrived. The other gunmen managed to get out of the building but were identified by witnesses as Nation members Norman 3X Butler (later known as Muhammad Abdul Aziz) and Thomas 15X Johnson (who later changed his name to Khalil Islam). All three were convicted of murder in March 1966 and sentenced to life in prison.

At trial, Halim confessed to killing Malcolm, but refused to identify the other two men who shot Malcolm that day. He told police, prosecutors and later, the court, that Aziz and Islam not the two men who helped gun down Malcolm X.

More than a decade later, though, with Aziz and Islam still serving time for a crime that all three men said they did not commit, Halim finally relented and named four other members of the Nation’s Mosque No. 25 in Newark as his co-conspirators. He signed affidavits once again asserting the innocence of Abdul Aziz and Islam, saying the two men were not involved. Prosecutors, however, declined to reopen the case.

In 1985, nineteen years after being locked up, Aziz was paroled. He continued to maintain his innocence, and in 1998, and went on to become the head of the Nation’s Harlem mosque. Islam was paroled in 1987, and like Aziz, continued to proclaim his innocence, but during his time in prison rejected the Nation’s teachings and converted to Sunni Islam. Islam died in August 2009, before his name was cleared. Halim also rejected the Nation’s teachings while in prison and he, too, converted to Sunni Islam. He was paroled in 2010.

For the two men the admitted murderer said were not involved, exoneration would take a lifetime. Last year, 55 years after thet were convicted, Islam and Aziz (now 83) were finally exonerated. An almost two-year long re-investigation into the assassination of Malcom found that the FBI and the New York Police Department withheld key evidence during the trial.

In a rare public admision, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. joined the men’s attorneys in asking a judge to toss out the convictions, and told The New York Times that the men did not get the justice that they deserved.

Indeed. For even though no physical evidence linked them to the crime, and despite Halim’s repeated professions that both Aziz and Islam were innocent, they were still prosecuted and convicted.

Based on other evidence, you say? Not so fast. What if the other evidence also said Aziz and Islam were not involved?

In 1963, in the case of Brady v. Maryland, the U.S. Supreme Court held that police and prosecutors are legally bound to turn over so-called “exculpatory” evidence to the defense before trial. Exculpatory evidence, of course, is almost any evidence that is favorable to the defense, like evidence that the defendant is innocent, or that someone else could be guilty.

Prosecutors have this duty in part because the law is supposed to be about the quest for the truth, not just another notch on someone’s belt.

If the Supreme Court says police and prosecutors are legally bound to disclose, that ruling becomes the law of the land. A refusal to do what the Supreme Court says is a violation of that law. Simple, right? There is a notion in American criminal jurisprudence that no innocent person should ever be unlawfully convicted of a crime.

Justice Edward Douglass White explained, in the 1895 case of Coffin Vs. United States (March 4, 1895) that the historical view of jurisprudence has always been that “It was better to let the crime of a guilty person go unpunished than to condemn the innocent.”

Unfortunately, we are along, long way from that ideal. Prosecutors routinely prosecute people when they hae in thir possession evidence suggesting they may not be guilty. It’s sneaky and it’s unfair, but truth and justice be damned. When prosecutors decide to hide exculpatory evidence the defense usually doesn’t even know it happened. This kind of behavior violates the public trust in the fundamental fairness of the criminal justice system.

So, what happens to those who are entrusted with enforcing the nation’s laws when they intentionally and actively engage in disobeying them? What happens to the betrayers of the nation’s trust when they fail to turn over evidence in accordance with Supreme Court rule? A stern talking to? In a rare case termination?

Are they not common– or perhaps, even uncommon– criminals at the point they willfully break the law?

In a statement, Innocence Project and civil rights lawyer David Shanies said, “Exonerating these men is a righteous and well-deserved affirmation of their true character.”

I guess that’s something. But if you’re taken off the street and locked up having done nothing wrong, I would argue that it’s tantamount to being kidnapped and held against your will. Where is the justice for the victim when the kidnapper is simply told “don’t do that again?”