President and CEO

National Urban League

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind.” — Toni Morrison, Nobel Lecture, 1993

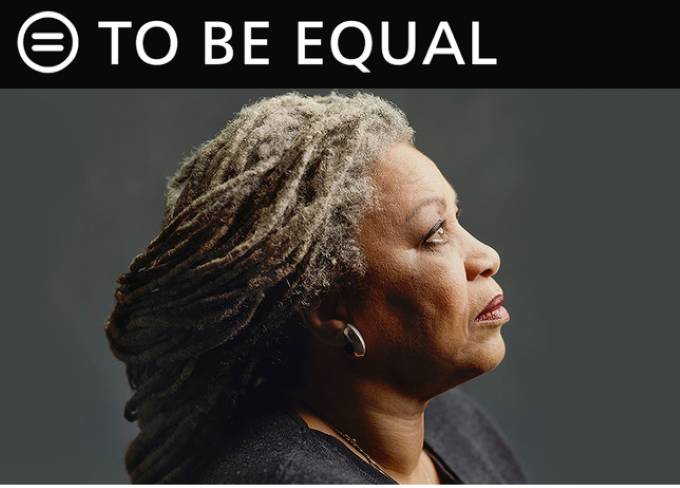

A few years after being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, for a body of work known for centering the Black American experience, Toni Morrison was asked by a white reporter when she would “incorporate white lives” into her books “in a substantial way.”

“You can’t understand how powerfully racist that question is, can you?” she asked. “You could never ask a white author, ‘When are you going to write about Black people?’ Whether he did or not, or she did or not. Even the inquiry comes from a position of being in the center.”

Morrison likened herself to a Russian author, writing in Russian, about Russia. “The fact that it gets translated and read by other people is a benefit, it’s a plus. but he’s not obliged to ever consider writing about French people, or Americans, or anybody.”

Morrison’s death this week, at the age of 88, is a loss not only to the literary world, but to the cause of racial justice and civil rights. And it comes at a time when her unique voice is especially relevant.

Shortly after the election of Donald Trump in 2016, she published an essay entitled “Make America White Again,” in which she argued that white America’s loss of “the conviction of their natural superiority” had led to its debasement. The slaughter of unarmed men and women of color at the hands of police and racially-motivated mass murder, the bombing of Black churches — and white America’s apparent tolerance for all of it — she asserted, were part of the death knell of white superiority.

“If it weren’t so ignorant and pitiful, one could mourn this collapse of dignity in service to an evil cause,” she wrote.

It is telling that what the interviewer noticed most about Morrison’s work was the absence of white characters; white privilege can be like air or light, notable only when it is absent. And according to Morrison, white voters were beginning to feel it ebb away.

“Toni Morrison” may have been as much a creation as her novels; she said she regretted using the nickname, derived from her chosen confirmation name, Anthony, and always thought of as Chloe, her given name. She grew up in the integrated town of Lorain, Ohio, and was disillusioned by what she saw as rampant colorism when she arrived at Howard University in 1949. Unlike classmates who had grown up in the south, she experienced legal segregation for the first time in Washington, D.C., but could not believe it was real.

“I think it’s a theatrical thing,” she told the New York Times. “I always felt that everything else was the theater. They didn’t really mean that. How could they? It was too stupid.”

When Morrison won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, it had been more than 30 years since an American-born author had won, but her status as the first Black woman honored overshadowed her Americanness.

And while she had complained that her work was more likely to be taught in women’s studies or African-American studies classes than in English classes, she hoped her work “fit first into African-American traditions and, second of all, this whole thing called literature.”

Today, even high-school students across the country are familiar with her work, reading her alongside Nathanial Hawthorne and Mark Twain. She has staked out the African-American experience as part of the broader American experience.

As politicians seek to divide us and racial violence swirls around us, it is this lesson – that Black America is America, that we must keep firmly in our hearts.

31TBE 8/8/19 ▪ 80 Pine Street ▪ New York, NY 10005 ▪ (212) 558-5300

Connect with the National Urban League

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NatUrbanLeague

Twitter: https://twitter.com/naturbanleague

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/naturbanleague

Website: https://www.NUL.org

Newsletter: http://bit.ly/SUBYT17

YouTube: http://bit.ly/YTSubNUL

Marc H. Morial is President and CEO of the National Urban League. He was a Louisiana State Senator from 1992-1994, and served as mayor of New Orleans from 1994 to 2002. Morial is an Executive Committee member of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, the Black Leadership Forum and Leadership, and is a Board Member of both the Muhammad Ali Center and the New Jersey Performing Arts Center.