-

29 July 2015

- From the section Science & Environment

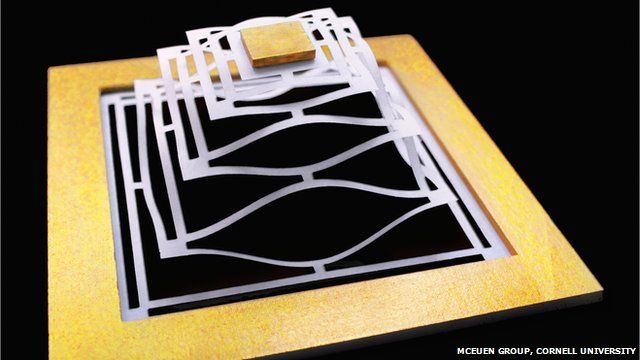

Graphene, a sheet of single carbon atoms, has been manipulated into tiny complex structures like springs using the paper art technique of kirigami.

Origami and kirigami, a sister technique where cutting is allowed, have increasingly influenced engineering and scientific research.

Some mechanical properties of graphene mimicked those of a sheet of paper.

The findings could pave the way to better flexible and stretchable electronics.

The research was carried out at Cornell University, New York, and published in Nature.

The team used micro-manipulators, or small remote controlled needles, to create the graphene structures.

“We also attached magnets to the structures and waved another magnet nearby, causing it to bend,” Prof Paul McEuen, lead author, told BBC Science in Action.

“The ratio of how stretchable versus how bendable paper was, was almost identical to that for graphene. The technical term for this is the Fopple-von Karman number but really it just tells you that, as a material, it will behave in a crumply and bendy way about the same as paper.”

Kirigami ideas can therefore be used to make micro-scale resilient and movable parts like stretchable electrodes, springs and hinges from graphene.

Unlike metals, which can lose their function if they are bent too much, graphene sheets are extremely robust. They can be stretched hundreds of times without degradation. The material is also much thinner than anything currently available for microelectronics so softer devices can be made which are more suited to being worn on the skin.

Of particular interest is putting these soft electronics onto nerve cells to see if they can sense the electrical impulses travelling between them.

As preceded by electronics, robotics is entering a trend of miniaturisation where graphene could play an important role.

Weighing scales

“If you want to measure the weight of a body, you can attach it to a spring and measure the elongation distance,” Nicola Pugno, professor of solid and structural mechanics at the University of Trento and involved in the Graphene Flagship at the Bruno Kessler Foundation, told BBC News.

“If you know the stiffness of the spring, you can calculate the weight. Similarly, if you know the stiffness of a graphene spring, it allows you to measure the force very precisely since the stiffness of kirigami graphene can be tuned up to very small values.”

This means the weight of very small particles can be measured accurately.

“The most important aspect of this paper is the experimental realisation of the nanoscale of this kirigami graphene. This is not simple from an experimental point of view,” said Prof Pugno.