The following is an excerpt fromOut of Sight: The Long and Disturbing Story of Corporations Outsourcing Catastrophe by Erik Loomis (The New Press, 2015):

The new environmental laws of the 1970s proved immediately effective. Between 1972 and 1978, presence of sulfur dioxide in the environment fell 17 percent, carbon monoxide by 35 percent, and lead by 26 percent.15 Americans lauded a future of jobs and health, prosperity and beautiful nature. Unions such as the United Steelworkers of America, who represented many Donora workers, the United Auto Workers, and the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers made alliances with environmentalists and promoted the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and other core legislation that protected all Americans, whether members of the working class or wealthy, from the emissions and pollutants of industry.

Environmentalists for Full Employment formed in 1975 to “publicize the fact that it is possible simultaneously to create jobs, conserve energy and natural resources and protect the environment.” When Ronald Reagan became president and cut OSHA and EPA funding, the AFL-CIO and Sierra Club created the OSHA/Environmental Network to organize resistance between the two movements. Environmentalists and a Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees local representing tannery workers in Fulton County, New York, overcame past differences and worked together on both the workplace environment of the tannery and tannery-created water pollution. By the late 1990s, workers reporting environmental violations and environmentalists helped the union develop plans to improve working conditions in the plants.

The potential for a strong labor-green coalition to fight for healthy workplaces and ecosystems clean enough for people to enjoy in their free time was a threat to corporations. Companies responded to environmentalism’s rise by taking advantage of a road the American government had already opened to them—moving their operations away from the people with the power to complain about pollution. They did this in two ways. Some industries scoured the nation, seeking the poorest communities to place the most toxic industries. They assumed those communities, usually dominated by people of color, would not or could not complain. The companies would work with corrupt local politicians to push through highly polluting projects before citizens knew what was entering their communities. Other industries went overseas, seeking to repeat their polluting ways in nations that lacked the ability or desire to enforce environmental legislation. Capital mobility moved toxicity from the middle class to the world’s poor.

In 1978, Chemical Waste Management, a company that specialized in handling toxic waste, chose the community of Emelle, in Sumter County, Alabama, as the site of its new toxic waste dump. Corporations contracted with Chem Waste to handle their toxic waste. Sumter County was over two-thirds African American and over one-third of the county’s residents lived in poverty, but whites made up the county political elite approving the decision. In Emelle, more than 90 percent of the residents were black. This is why Chem Waste chose Emelle. They worked with a local company led by the son-in-law of segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace to acquire the site. No one told local residents what was to be built there. Local rumors suggested a brickmaking facility. The company dumped polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and other toxic materials at the site. Despite claiming it was safe, the company racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines. Such activities were common for Chem Waste. It always chose communities like this to site its dumps—Port Arthur, Texas, in a neighborhood that was 80 percent people of color; Chicago’s South Side in a neighborhood 79 percent people of color; and Saguet, Illinois, a 95 percent African American area.

[quote]African American neighborhoods are routinely zoned for garbage dumps and landfills, and petrochemical companies locate cancer-causing chemical plants in black communities along the Mississippi River.[/quote]

The racist actions of companies like Chemical Waste Management led to the environmental justice movement. By fighting for the environments where we live, work, and play, environmental justice has redefined environmentalism and connected capital mobility with environmentalism by focusing on how corporations make decisions about where to locate toxic exposure. Through the environmental justice movement, people of color began adapting the language of environmentalism to their struggles with toxicity and pollution. Scholars usually date the movement to an incident in 1982 when the state of North Carolina wanted to dump six thousand truckloads of toxic soil contaminated with PCBs in a predominantly African American section of Warren County. More than five hundred protesters were arrested. Civil rights leaders and community members began tying racism to environmentalism, noting how the Environmental Protection Agency in the Southeast had targeted African American communities for toxic waste dumping. A new social movement was born.

Alabamians for a Clean Environment formed to fight the Emelle toxic waste site. Chemical Waste Management had built a toxic waste dump in Kettleman City, California, a 95 percent Latino town in a white majority county. When the company planned to add a toxic waste incinerator, residents fought back, forcing Chem Waste to withdraw its application in 1993. Residents and the company still battle over environmental justice there today. African Americans in Anniston, Alabama, won a lawsuit against the chemical company Monsanto, which paid $390 million in 2003 for contaminating their neighborhood with PCBs, while residents of Norco, Louisiana, defeated Shell Oil in court, forcing it to pay for them to move away from the neighborhood the oil giant contaminated.

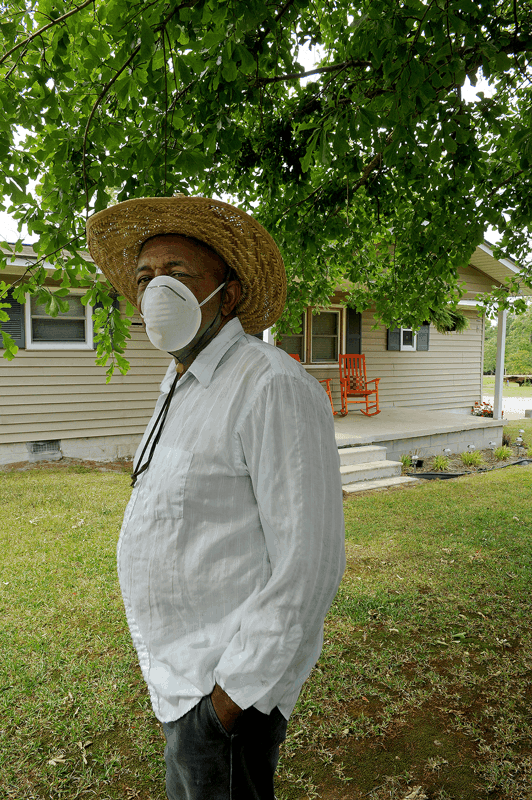

The environmental justice movement has not forced widespread changes in corporate strategies. Corporations still seek out the areas with the poorest people to dump toxic waste. The people of the Hyde Park neighborhood of Augusta, Georgia, have conducted a long campaign for environmental justice against a wood-preserving factory that dumped dioxin-laden wood-treatment chemicals into groundwater as well as against a ceramic factory that emitted dust across their yards, resulting in skin conditions, circulatory problems, and rare forms of cancer. The neighborhood near these factories is almost entirely African American, leading residents to believe their neighborhood was targeted for this exposure.

African American neighborhoods are routinely zoned for garbage dumps and landfills, and petrochemical companies locate cancer-causing chemical plants in black communities along the Mississippi River. Poverty and race too often mean toxic exposure and cancer in the United States. In a 2014 report, researchers at the University of Minnesota demonstrated that people of color in the United States breathe in air 38 percent more polluted than whites. In the Los Angeles metro area, 91 percent of the 1.2 million people who live less than two miles from hazardous-waste treatment facilities are people of color. Environmental inequality is a systematic problem made worse by intentional corporate decisions to profit off of poisoning minority populations.

While some companies target sites within the United States to dump pollution, more commonly, corporations either move production overseas or ship waste abroad. Free trade agreements lack meaningful environmental standards. After NAFTA’s passage, the American and Mexican governments engaged in meetings to plan for environmental problems, but corporations remained off the hook for their actions in Mexico. Twenty years after NAFTA, nothing has changed. Corporate control over the American government continues to ensure that trade agreements do not include environmental restrictions on corporate actions.

In the 1970s, with the first factories already going overseas, corporations began blackmailing workers, saying that increased environmental restrictions would force them to close their mills and move. This job blackmail provided a very effective strategy for corporations, allowing them to retake the pollution initiative from environmentalists and making workers scared pollution reduction would cost them their jobs. During a hearing for the Water Quality Act of 1965, St. Regis Paper Company president William R. Adams told a congressional committee, “The general public wants both blue water in the streams and adequate employment for the community. The older plant may not be able to afford the investment in waste treatment facilities necessary to provide blue water; the only alternative may be to shut the operation down. But the employees of the plant and the community cannot afford to have the plant shut down. They cannot afford to lose the employment furnished by the operation.” Such statements became ever more common after 1970, and workers believed them, fearing that placing scrubbers on smokestacks or limiting the dumping of chemicals in water would lead to the end of their jobs. They didn’t want to get poisoned, but they needed to eat and buy their children clothes.

Companies began viciously using environmentalism as an excuse for shuttering plants they intended to close anyway. In 1980, the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) announced the closing of its Anaconda, Montana, smeltery. It claimed it could not “satisfy environmental standards” the government now required of smelters. Workers were furious at environmentalists. But within a week, it came out that both the federal and state governments had offered to work with ARCO, granting it an extension or offering any concessions it wanted to stay in the state. The company refused. ARCO lied about a decision made to maximize profit. Usually, these nefarious lies went unchallenged, and environmentalism increasingly became seen as an elite movement unconcerned with the fate of American workers.

Corporate mobility cleaved unions from environmentalists. In 1976, UAW president Leonard Woodcock noted that job blackmail was a “false conflict.” However, “to a worker confronted with the loss of wages, health care benefits and pension rights, it can seem very real.” For example, in 1977, environmentalists and the United Mine Workers of America mostly agreed on an amendment to the Clean Air Act that would limit sulfur dioxide after environmentalists supported forcing corporations to place scrubbers on eastern smokestacks rather than mandating that lower sulfur coal be mined by nonunion labor in the West. But in 1990, the two interests could not agree on amendments for further emissions restrictions to fight acid rain. Coal companies increased their investment in the nonunion western mines as a result.

Companies began playing states off one another in a national race to the bottom. When the Belcher Corporation announced the move of its Massachusetts-based foundry to Alabama in 2007, the company’s chief financial officer stated, “The environmental regulations aren’t as stringent in Alabama as they are in Massachusetts.”

NAFTA and other trade agreements empowered corporations to follow through on their job blackmail internationally. A 1990s survey of American companies with factories in Mexicali, just across the U.S.-Mexico border, showed 25 percent moved to take advantage of lax environmental regulations, while 80 percent of furniture makers who moved from Los Angeles to Mexico in the late 1980s did so to reduce their environmental costs.

NAFTA and other trade agreements empowered corporations to follow through on their job blackmail internationally. A 1990s survey of American companies with factories in Mexicali, just across the U.S.-Mexico border, showed 25 percent moved to take advantage of lax environmental regulations, while 80 percent of furniture makers who moved from Los Angeles to Mexico in the late 1980s did so to reduce their environmental costs.

American companies poisoned the water of northern Mexico. As Matamoros, just across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, grew with the arrival of American-owned factories in the 1970s and 1980s, citizens had new economic opportunities but were also sickened by the emissions no longer allowable in the United States. Near one chemical operation, xylene levels in the water were more than fifty thousand times the level allowable in the United States, and behind a General Motors plant nearby, xylene levels were six thousand times the American legal limits. The effects of this crossed the border—water and air pollution do not respect national boundaries. Birth defects in both Matamoros and Brownsville skyrocketed, particularly cases of anencephaly, a condition that leads to babies with undeveloped brains.

NAFTA made these problems worse. In the years after NAFTA, more than 2,700 new maquiladoras were built along the U.S.-Mexico border. They rose without the infrastructure to service such large factories and the cities needed to house their employees exploded. Sewage disposal quickly became a major issue in northern Mexico. Air pollution meant both corporate profit and over 36,000 children in Ciudad Juárez emergency rooms between 1997 and 2001 due to breathing problems. Mexican federal spending on environmental protection fell by half between 1994 and 1999 at the same time that American corporations polluted that nation like never before. Mexican law mandates that toxic waste produced for other nations’ companies be exported back to the home country, but only 30 percent of this waste is actually returned to the country of origin. Corporations generate 80 million tons of hazardous waste in Mexico every year, and the economic costs of environmental degradation equal approximately 10 percent of Mexican gross domestic product. American corporations take little to no responsibility for any of this.

When we think of air pollution today, we probably envision China, which exports its steel to the United States and other nations while its citizens literally choke to death on the legendary smog. Over the objection of environmentalists, labor organizers, and human rights advocates, China received most-favored-nation trading status in 2000 with the United States. The Clinton administration claimed that China would advance on environmental standards if the standards were voluntary. It was wrong. Mickey Kantor, President Clinton’s chief trade negotiator, now calls the lack of environmental safeguards in the deals he worked on a “big mistake.”

These agreements have helped worsen the greatest environmental crisis of the twenty-first century: climate change. A 2014 UN report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change showed that greenhouse gas emissions grew twice as fast in the first decade of the twenty-first century as in the previous three decades. Too often, Americans point to China or India as the drivers of these emissions to say there is nothing we can do at home, but in fact much of the emissions in Asia come from burning coal for factories producing goods for American and European markets. The UN report stated, “A growing share of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion in developing countries is released in the production of goods and services exported, notably from upper-middle income countries to high-income countries.”

In January 2014 alone, the United States imported 3.2 million tons of Chinese steel. American corporate interests do not own these Chinese steel companies, but they do own thousands of other heavily polluting factories in China. These corporations want to avoid “environmental nannies,” as Linda Greer of the National Resources Defense Council has been called. The Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a leading Chinese environmental NGO, released a report in October 2012 detailing the massive pollution by apparel factories that contract with U.S. corporations, including Disney. The report noted that subcontractors for Ralph Lauren discharge wastewater filled with dyes and other pollutants into streams and do not use pollution-reduction devices on coal boilers, releasing extra pollutants into the air. Chinese citizens protest the pollution, but their government has little tolerance for these protests, which pleases foreign investors. A recent scientific estimate shows that in 2006, U.S. exports were responsible for 7.4 percent of Chinese sulfur dioxide, 5.7 percent of nitrogen oxide, and 4.6 percent of carbon monoxide. According to the World Health Organization, 2.6 million people in southeastern Asia, mostly in China, died of outdoor air pollution in 2012. How many of those lives could be saved with better environmental standards on products imported to the United States? American companies may not be responsible for all the suffering of the Chinese working class from pollution, but they certainly contribute to it.

Although the United States has outsourced its air pollution to China, Americans still suffer the results. Some of the polluted Chinese air follows wind currents across the Pacific to the western United States. Although Los Angeles has done much to improve its smog in recent decades, Chinese air pollution is again making L.A. air unhealthy. A 2014 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science showed that 12 to 24 percent of sulfates in the American West come from drifting air pollution from Chinese production for the export market, enough to occasionally bring Los Angeles above federal ozone limits. As Steve Davis, co-author of the study, told the Washington Post, “We’ve outsourced our manufacturing and much of our pollution, but some of it is blowing back across the Pacific to haunt us.”

Americans may unknowingly deal with a smidgen of this pollution, but people who live near these factories deal with far worse. The people who live near the Rana Plaza factory site in Bangladesh where 1,100 workers died in April 2013 have to live with more than just the heartbreak of losing friends and family. They also have the daily struggle of massive pollution. Dyeing clothing requires water and creates pollution unless regulations force companies to clean it up. If the contractors American apparel companies use had to follow something similar to American environmental standards when producing for the American market, the dyeing problem could be mitigated, and the world’s poor could have industrial jobs without being poisoned. The Clean Water Act includes regulations about dyes. This has made American waterways cleaner and people healthier. Alas, such an outcome was unacceptable for the clothing companies.

Many dyes use sulfur that creates rashes on workers’ skin and remains in water supplies even after chemical treatment. In the 1990s, the Mexican state of Puebla became a center of blue jeans production. Tehuacán was once known as the “city of health” for its natural springs. No more. The companies dumped blue dye into nearby water supplies. Soon the water ran a dark indigo, not coincidentally the color of a pair of dark blue jeans. The water was then used for irrigating fields, where the blue dye burned seedlings and destroyed crops.

Today in Savar, Bangladesh, near the site of the Rana Plaza disaster, the water runs different colors from the textile factories, depending on what the factories are doing on a given day. Sometimes it is red. Sometimes purple. Sometimes blue. As they used to do in the United States before environmental reforms, the textile manufacturers just dump their dyes into the rivers, killing almost all aquatic life. Near the polluted canal in Savar is a school. But the students struggle to learn. The rank smell from the pollution wafts over the school, causing debilitating headaches. Nearby are two garment factories, two dyeing factories, a textile mill, a brick factory, and a pharmaceutical plant, almost all making products for the Western market. Bangladeshi tanneries producing leather for China, Europe, and the United States impact the ecosystem in similar ways, with chromium and other pollutants contaminating groundwater, fouling rivers, and emitting benzene, hydrogen sulfide, and other noxious gases into the air. Places like Savar are what some scholars call “sacrifice zones.” Wealthy corporations have chosen these places to bear the environmental and health burdens of producing wealth for the world’s elite. Local people do not benefit from this system. The limited benefits of low-paying, dangerous work are outweighed by the massive sacrifices the local residents pay in discomfort and illness.

Erik Loomis is a professor of labor and environmental history and a blogger at Lawyers, Guns and Money.