A rose by any other name . . .

We’ve all heard this familiar paraphrase of a line from William Shakespeare‘s play Romeo and Juliet. The reference is most often used to suggest that what one calls a thing does not change what it actually is.

On March 18, 2018, Stephon Clark was shot and killed by Sacramento Police Officers Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet in the backyard of his grandmother’s house. The officers said they shot Clark because they believed he had pointed a gun at them. The “gun” turned out to be a phone. Why anyone would point a phone at the police is an always-unanswered question in these cases, but they said that’s why they shot him seven times– three times in the back. The district attorney said they were legally justified in the use of deadly force.

When fired Minneapolis police officer Jeronimo Yanez was acquitted of manslaughter charges in the killing of Philando Castille– caught on camera by both police dashboard camera and a live video stream by Castille’s girlfriend Diamond Reynolds, both President Barack Obama and Minnesota governor Mark Dayton were surprised. Gov. Dayton asked the question everyone else was asking: “Would this have happened if the driver were white, if the passengers were white?”

All other things being equal, why is it that blacks are more likely to be killed by police in situations where whites would be politely engaged?

Just this past Sunday, at a protest in Chicago over the killing of George Floyd, a white man armed with a customized AR-15 showed up. He was clothed in tactical gear, and according to protesters pointed his rifle at people’s faces. He was flagrantly breaking the state’s open carry law. Video of the incident showed police talking with the man and then politely sending him back home. After he left police went back to running down unarmed protesters. Same response if he had been black? Not likely. Stephon Clark was killed for carrying a phone.

Why the disparate treatment? This bending over backward that police officers do in dealing with whites in America can be capsulized, in my opinion, in one word: RESPECT. The age-old argument, after all, is that it can’t be called racism when black cops kill blacks.

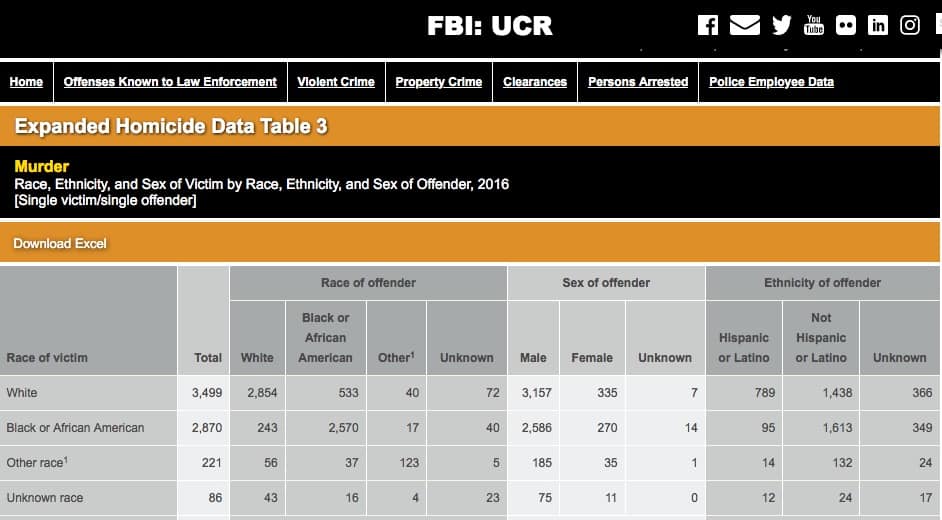

There is no discounting the fact of black-on-black crime, but that charge is in actuality a non-starter, since both blacks and whites kill predominantly within their respective groups.

What is damning to this nation is the continuing assault by police all around this country on one group of people under the color of the law. Beatings, shootings and lynchings have been ignored, rubber-stamped or carried out by people cloaked with “lawful authority” since the first blacks were forcibly inserted into this land.

This stain on America’s soul– the institution of slavery– produced a picture of a people codified in the law as less than human and completely unworthy of respect. And the US Supreme Court said so– without equivocation– more than 160 years ago.

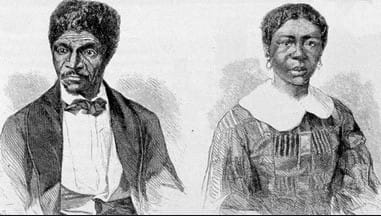

The year was 1857. The entire nation was embroiled in an on-going and bitter debate about a case that had made its way to the United States Supreme Court. Dred Scott, a man born into slavery in 1799, and his wife, Harriett, had sued their owner for their freedom based on a Missouri statute that said 1) a slave had a right to sue for his freedom, and 2) that any slave who had been taken to live in a free state was automatically made free and could not be returned to slavery.

Scott and his wife fit the bill perfectly. They had been taken to free states numerous times by their masters. Both were illiterate but had the support of many powerful people, who helped with legal fees and other support. They filed suit in St. Louis Circuit Court in April 1846 and lost on a technicality. The case was retried in January 1850, and the Scotts were declared to be free.

The owner’s widow, Irene Sanford, appealed the decision, and in 1852 the state Supreme Court sided with her, making the Scotts and their children slaves once again.

The following year, in November 1853, Scott filed a lawsuit in the federal courts, challenging the ruling of the state supreme court. On May 15, 1854, the United States Circuit Court for the District of Missouri heard the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford and also ruled against the Scotts, denying them the freedom they were so desperately seeking. In December 1854, before the year was out, Scott appealed the federal court’s decision to the highest court in the land.

By this time the case was being widely followed. The question of the right of any slave to sue his master for freedom was being hotly debated and fanning the flames of rebellion throughout the slave-holding states. Abolitionists became increasingly vocal about the despicable institution of slavery, while slaveowners and wannabe slaveowners alike chafed at what they argued was northern-influenced interference in southern affairs.

With this backdrop, the eyes of the nation were fixed on the high court. The Court was itself predictably divided. Both proslavery and antislavery justices were on the bench, but the Southern justices had a majority. The case was argued on February 11, 1856, and 23 days later, on March 6, the Court handed down its decision: the Scotts would remain the personal property of their “owners.”

In reaching this holding– which had far-reaching implications for every person of color in the nation– the Court made a sweeping pronouncement that re-energized and emboldened the pro-slavery point of view. Any law attempting to limit slavery in any state would fail because, the Court said, Congress had no power to prohibit slavery. And blacks who were either themselves slaves or whose ancestors had been slaves were not entitled to the rights of an American citizen and could not sue anyone in federal court.

These next words, though, memorialized for all time in the High Court decision, put flesh on the bones of the pro-slavery argument: “[Blacks] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect;”

Maybe I’m wrong, but I believe this sentiment, however much it has been relegated to the trash heap of unspoken utterances, is still alive and well in America. It’s evident in the callous disregard displayed by those for whom black life is unredeemable and without value. It is seen in this context most often in the form of police brutality, but is not a uniquely white reaction to all things black.

Because black people disrespect black people, too.

We see it in the form of out-of-control black-on-black crime. We see it in the socially accepted breakdown of the family (i.e., missing fathers and a shameful explosion of “baby mamas”). We see it in the large-scale practice of abortion within the black community when neither rape nor incest is involved (yes, women have the absolute right to choose, but how hard is it really for adults to NOT get pregnant if they don’t want to have children?). Black lives– ALL of them– do matter.

Black folk have drank deeply of ‘the Kool-Aid of no respect’ for generations, and have internalized the same view of themselves that the Supreme Court expressed 163 years ago; the same view expressed by the first American slavemasters back when Plymouth Rock landed on us. We see it in the way we refer to our women as “bit***s” and “hoes.” Fundamentally, we’re still “niggas” in our own eyes.

The commission of serious crime by any protestor cannot be condoned. Indiscriminate looting and the destruction of businesses in the local communities has no place. But there are many in the world of protest who believe that the loss of millions dollars can be a powerful incentive for municipal change.

There is something wrong with a system that allows police officers to “legally” execute a defendant for a crime that no judge could lawfully sentence him to. According to data compiled by Mapping Police Violence, a research and advocacy group, blacks are 2.5 times as likely as white Americans to be killed by police, but make up only 13 percent of the population.

In Minnesota, blacks are only 5 percent of the population, but 20 percent of those killed. In Utah, blacks are just 1.06 percent of the population but make up 10 percent of all police killings over the past seven years.

While California, Florida and Texas have the highest numbers of killings of Black people by police officers, when you adjust for population size and demographics, blacks are more likely to be killed by police officers than whites in just about every state in the nation. No study or report is necessary to convince blacks of this fact.

The institutional nature of this attitude results in minorities like Hispanics (like Jeronimo Yanez– who killed Philando Castille), Asians (like Tou Thao– who stood guard while Derek Chauvin, Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng squeezed the life out of George Floyd) becoming part of historically all-white police forces and taking on the same disdain and lack of respect. Blacks cops get caught up, too.

In fact, Charles Menifield, dean of the School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University–Newark argued forcefully a couple of years ago that “[t]he killing of black suspects is a police problem, not a white police problem.” There are a number of black men in America today who can attest to that. Generally speaking, police officers are all too often expected and encouraged to treat “you people” without civility, common decency or respect.

Tyrone Dodson, a retired police officer who served with the Washington DC Metropolitan Police Department for 29 years, said:

“Because I was a police officer of almost 30 years, I get upset about police officers being killed. But I do get outraged when police officers don’t do the right thing and are hasty in their decisions and kill somebody, not being responsible. Sometimes I think it’s murder, which police officers do. For so many years, police officers have been getting away with murder, unfortunately. I hate to say that, but because of the system, the U.S. attorneys, they will take the police officer’s word as being valid and truthful. As years have gone by, in some cases it hasn’t always been true.”

Some say that the problem with blacks dying in encounters with police is not racism, but an “entrenched set of biases and assumptions that pervade police forces.” I say a rose by any other name is still a rose. The explanation only begs the question: from where do these entrenched sets of biases and assumptions ultimately come?

The action taken by local authorities after Floyd’s killing– firing and charging Chauvin, Lane, Kueng and Thao– is the only way to ameliorate this systemic problem. Officer accountability is a policy that needs to be made a part of every police department’s operations manual. It comes too late for George Floyd, but it may save the life of another George Floyd tomorrow. You can’t stop racists from being racist– but you can impact their behavior and make them treat other people with respect.

Only when officers understand that their actions will have consequences: that jobs will be lost and their families made to suffer through their criminal and civil prosecution; that they are no longer institutionally protected against their knowing wrong-doing and that disrespecting the people they are sworn to protect and serve will send them to the place where no one gets respected– only then will real change come.

Just ask Dred.