Perhaps former general and now Trump Chief-of-Staff John Kelly doesn’t know his history. To concede that possibility is the kindest way of explaining his ignorance on the subject of the American institution of slavery and its tortured political demise. Otherwise, we’d be forced to brand him a fool.

Kelly recently said– publicly, mind you– that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War.”

I’m not sure who he thought couldn’t offer up a compromise position– or who he thought was responsible for failing to agree, but if I understand him on this point, he believes that a compromise on slavery was just what we needed to prevent the Civil War.

In a word: incomprehensible.

In point of fact, a “compromise” position on slavery had been reached. It was proposed by Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio, approved by both Houses of Congress and signed by President James Buchanan on March 2, 1861.

It did not stop the Civil War.

Instead of the 13th Amendment we now have, abolishing slavery, the Corwin Amendment was intended to be “the” compromise measure designed to 1) convince the 7 states that had already seceded to come back to the Union, and 2) to keep those states that were threatening to secede from doing so.

It read: “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of person[s] held to labor or service by the laws of said State.”

Corwin’s “compromise” was to allow slavery to continue in the states where it existed– for all time to come. The compromise caveat was that slavery would not be allowed to spread to non-slave states. It is both tragic and sad that a man like Kelly, with such a mindset, occupies such an important position in a White House administration.

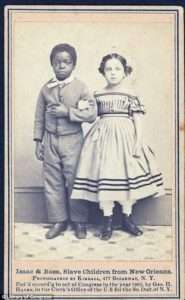

The Corwin Amendment would have created a permanent class of people born in this country whose children and grandchildren would have never been able to escape being enslaved. As a “compromise,” it never considered the slaves. And on its face, it did not deal with what would happen to free blacks kidnapped by marauding slave traders and forcibly taken into the ‘forever-slave’ states.

The quick passage by the Congress of the proposed legislation clearly shows there was considerable support for the ‘compromise.’ Even Abraham Lincoln was prepared to accept the amendment if it meant preventing civil war. Arguably the country’s most ardent opponent of slavery’s expansion among the ranks of public figures, Lincoln spoke briefly about the amendment during his inaugural address, saying: “I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.”

A few northern states quickly signed on to the amendment, content with not having slaves brought into their territories and unsure about how or whether it was proper to force other state lawmakers to discontinue the practice. This ‘states right consideration’, after all, was the primary argument of all the slave states: that every state had the right to decide what was allowed and permitted inside its own state lines.

The ‘state’s rights’ argument was widely used in support of maintaining the institution of slavery. Many years later it was also be raised to support the Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, segregated schools and public accommodations, and the hate-filled actions of the KKK.

Apparently, the southern states wanted no restrictions of any kind on where slavery could exist in the nation because despite Lincoln’s acquiescence to “the compromise,” southern regiments fired on Fort Sumpter on April 12, 1861. With that act, all action on the amendment stopped, as the nation erupted into civil war. As a result, the amendment never became law.

Kelly seemed to be saying that such a “compromise” would have been a good thing for the nation. But morally speaking, how do you compromise on slavery? How can “slavery over here, but not over there” provide a framework for confronting the very existence of the institution?

Kelly explains: “It’s inconceivable to me that you would take what we think now and apply it back then. I think it’s just very, very dangerous. It shows you what — how much of a lack of appreciation of history and what history is.”

For Kelly, it’s wrong to judge people who believed in owning slaves because they lived in another day and time. History was just a little bit bigger than Kelly remembers it, for people back then both in the South and in other parts of the country had the same view of slavery that most of us have today. The abolitionists, the “slave sympathizers,” and religious groups like the Quakers thought slavery was an odious institution. The people Kelly is referring to– those who today oppose what slaveowners and would-be slaveowners did then, would probably fit comfortably in the category of an abolitionist in 1861. So taking what we know now and applying it back then would not be too big of a stretch.

The brutality of slavery as it existed at the time of the Civil War was just as offensive an institution as it is today. Following Kelly’s logic, however, human slavery as we know it now– kidnapping and luring children and women off the streets and forcing them into prostitution and slave labor camps– should be equally ripe for a “compromise.”

Kelly went on to say: “I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days.”

And that mindset– state’s interests first– remains the credo of the same groups of people in America today, as demonstrated by the continued raising of the Confederate flag: which is the flag of treason and rebellion against the USA.

We understand that some of the Founding Fathers were slave-owners. But the principles and values that undergirded the new nation, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, constituted the vision of an America that all of them intended that it one day would come to be. One in which “all men are created equal, . . . endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, [and] that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” This is a vision of America that would have been made permanently impossible to realize under a slavery “compromise.”

Like Trump, Kelly seems to celebrate the good in evil: “[M]en and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had to make their stand.”

One can get comfortable in anything. Darkness, after all, is an all-consuming state of existence. It explains why many ‘honorable’ southern men had their wives pack lunches and traveled miles with their children to spread out blankets under the big oak tree and eat while witnessing the lynching and burning of black men. But wait, I digress.

Kelly would call men who celebrated brutally depriving other human beings of the unalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness– men who were willing to risk their lives defending such a despicable institution– “honorable.” I just can’t bring myself to do it.

Historians don’t usually focus on how slavery impacted “honorable men” like Lee. The toll paid by blacks is well known and certain, but the psychological toll paid by whites is rarely if ever, talked about.

It is well-known that slavemasters routinely raped their female slaves. The sheer number of “light-skinned” blacks who walked off the plantations prevents any and all claims to the contrary. Both the slavemaster and his knowingly compliant wife participated in a system that allowed white men to sire black children in one breath and then enslave and sell them in the other. How vile and corruptible is that?

How ‘honorable’ is it to support an institution that permitted a man to enslave and sell off his own offspring?

It is to his great credit that President Lincoln– despite his own internal demons– signed the Emancipation Proclamation with all of its flaws, because by it, slaves over time were freed from slavery, and slavemasters were freed from themselves.

[An excerpt of this column appears in the print version of the Orlando Advocate.]